Historic Map Compiling Project – Le Plan Scénographique de Lyon

– Gigapixel image of the compiled full map browseable in Zoomify viewer

– Side-by-side comparison of the 1548 map with five historical derivatives

– High-resolution 3D (bird’s-flight) video tour of the full map

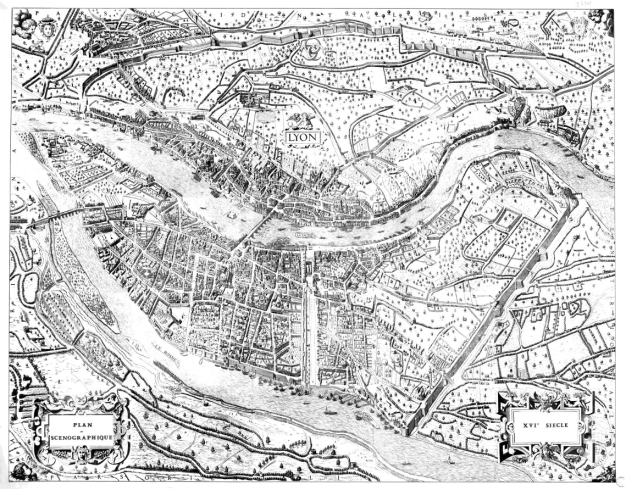

In January 2014 I digitally optimized and compiled the 25 separate sheets that together make up “Le Plan Scénographique de Lyon vers 1550,” a huge, highly-detailed, 16th-Century axonometric (bird’s-flight view) map depicting the French city of Lyon cc. 1544-53 CE. Since then I’ve been working to understand and contextualize this curious historical artifact, and this essay is one product of that effort.

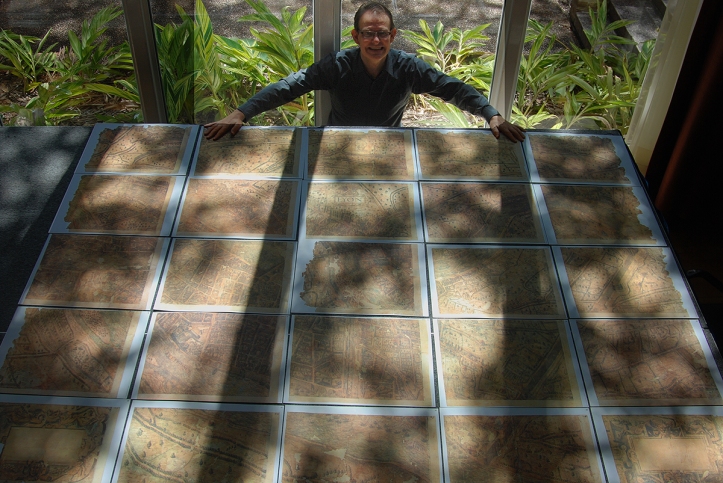

The Archives municipales de Lyon holds the only known copy of the 1550 Plan Scéno (as I’ll call it here, though many of the preparatory drawings likely date to 1544). In 1989 preservationist and paper expert Michel Guet dismantled and restored the map. This involved detaching the 25 sheets from their paper backing and each other as well as removing the remnants of earlier flawed restoration efforts. In 1990 the Lyon Archives published photographs of the 25 separated and restored map sheets along with an accompanying volume of scholarly essays (later augmented with a second set of essays). All of the essays from the project were hosted on the Lyon Archives’ website for years and are still accessible via the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine. If any photographs exist of the plan taken before Guet’s 1989 restoration they have not been published by the Lyon Archives.

The map segments are to be arranged for viewing in a 5 by 5 grid starting from the top left, each segment being overlapped by the segments to the right and below it. Because each segment of the published map is larger than the flatbed scanner I used, I originally scanned each segment in two parts at 600 ppi, combined them, and then reconstituted the full map using Adobe Photoshop (info tooltip | link).

Viewing the map’s 25 segments separately, it is very difficult to effectively view or even fully conceptualize the map in its totality, as a single composition. To redress this I determined to compile the 25 map segments into one contiguous digital image. I should note that significant image adjustment (aka warping) was required in some areas to insure that the segments line up logically and so the final product would appear seamless. You’ll notice that the bottom-right cartouche is slightly lower than the one on the lower left. This may not be a characteristic inherent in the original, but could reflect the digital processing – I mostly compiled each row of sheets starting from the top-left, following the original numbering of the 25 sheets, and therefore the bottom-right sheets were the last added to the composition.

For modern viewers, the faux-aerial perspective used for pre-modern axonometric city maps is strikingly similar to the satellite-derived views provided by modern online map services (though the top of the the 1550 Plan Scénographique is primarily directed west-southwest, not north). For comparison, below is a high-contrast screenshot of Bing maps’ “Bird’s Eye view” of modern-day Lyon (facing west) compiled from multiple aerial photographs taken at an oblique 45-degree angle (unfortunately this bird’s eye view is now only available via the Windows Maps desktop app – AT 02/21)).

Note that the modern shape of central Lyon is significantly different from that shown in the 1550 Plan Scénographique. This is primarily because of the largely-industrial Perrache neighborhood, extending South (left) of the highway in the modern center of the Presqu’île (peninsula), which did not exist in the 16th century. Perrache was developed from 1779-1840, incorporating southern marshland and small islands into the peninsula and moving the confluence of the Saône and Rhône rivers further downstream (source). In the sixteenth century, these low-lying islands were repeatedly flooded, destroyed, and rebuilt by the rivers. Only the edge of the area now covered by Perache is shown on the 1550 Plan Scéno, an island labelled “[BRO]TEAUX D’ENEY” in reference to the nearby Abbaye d’Ainay. I haven’t attempted to recreate how Broteau D’Ainay might have looked in 1548, but it can be seen on Philippe Le Beau’s 1607 Lyon map (optimized detail view with label indicated). Source: archives municipales de Lyon.

See Gauthiez (2010) for more on Perrache and the confluence and Arlaud (2000) for much more on the Presqu’île.

Lyon Topographic Plan, 1544 & 2015

The animated map above is an augmented “mashup” incorporating three sources –

- A blueprint of Lyon in 1544 (identified as a/the main year during which the Plan Scénographique’s survey drawings were made) adapted from a Flash presentation accompanying the Lyon Archives’ 2009 exhibit Lyon 1562: Capitale Protestante (B. Gauthiez) superimposed on

- Geoportail‘s amazing elevation map (“Carte du Relief” layer, unfortunately there was no altitude legend), facing west and extended North and South, and

- a 2015 satellite image exported from Google Earth Pro.

An observation about the above GIF – I originally labeled the top-right neighborhood (quartier) around Le Couvent l’Observance “Vaise.” Vaise is actually the name of the faubourg (suburb) located outside Lyon’s northern city gate (“Porte de Vaise“), situated on a plain north of l’Observance and west of the Saône river which was mostly farmland in the mid-1500s. During the 16th century the area around l’Observance was named “Le clos des Deux-Amants” after a Roman-era funeral monument shown on the Plan. (source: Les Cordeliers de l’Observance á Lyon, par L.A.A. Pavy et [C.] Tissseur, 1836, pp.6-11).

Click here to see the area on the digital Plan Scéno (top half of sheet 10), and from there you can switch to the 1698 and 1876 derivative maps (select from lower-left pulldown menu) to see the now-missing part of the 1550 Plan Scéno showing the approach to Vaise.

Where Lyon ends and Vaise begins is confusing because it changes over time. As Lyon grew northward the city would build a new city gate and absorb the part of “Vaise” located south of the gate. In 1550, the city gate labeled the “Porte de Pierre-Scize” on the 1550 plan was the northernmost city gate of Lyon and was sometimes referred to as the “Porte de Vaise.” In 1580, another gate was built at a point just north of the edge of the 1550 plan and this gate becomes the “Porte de Vaise” (it would also sometimes be called “Porte du Lyon” or “Porte neuve du Pont Levis” (source).

This annotated detail taken from LeBeau’s non-derivative 1607 map of Lyon extends further north than the 1550 plan and shows more of Vaise (a half-century later):

“Why not georectify the Plan Scéno, since we know where most of the represented landmarks were located, maybe even all of them?”

Because the map is far from spatially accurate. The area of the W-SW-facing map overall appears to be significantly stretched N-S (the X-Axis) compared to the real-world dimensions. This uneven stretching is most notable in the bend of the Saône river as it rounds the central hill of Fourvière, which is far less sharp than in the real world. This may have been deliberate artistic license rather than a mistake, as the elongation allows the cartographer more left-right room to include location-based labels and imagery, particularly along the densely-settled banks of the Saône. It also would reflect the viewpoint of an artist situated on the hillside of La Croix-Rousse, looking south across the Saône towards Château de Pierre-Scize making preparatory sketches. Scholars have also observed that while many buildings had as many as five or six floors, the map shows no building as having more than four.

While I do believe that the 1550 Plan Scéno de Lyon achieves verisimilitude as a portrait of the city (achieves the appearance of spatial accuracy), it’s building imagery is not completely reliable, and both its scale and compass directionality are wildly inconsistent.

This plan was drawn up by calculating angles from certain heights, particularly church towers such as that of Saint-Nizier which, located on the peninsula, has often been used for this purpose. These calculations were then compared with distances on the ground, measured by using a knotted rope or by counting the number of steps…in the geometric center of the plan was the ditch, drawn according to a scale of 1/824. All around, everything is out of proportion in order to include certain elements considered essential. If the [1/824] scale had been used throughout, the plan would have been 3.5 times bigger!

—Musée Gadagne, A plan depicting scenes of 16th C. Lyon, Inv. N 1675

Geographer and urbanist Bernard Gauthiez, the de facto topographical biographer of Lyon for the past twenty years, expressed it to me thus:

“Georectify[ing] the 1544 plan [is] like mapping the Near East from the Bible… Several scales are used, and it has not been drawn from a measured survey. See my paper on it.”

Professor Gauthiez’ work on Lyon (along with the Archives Municipales’ 1990 publication) is an authoritative modern source for many of the ideas I am exploring regarding the topography and urban development of pre-modern Lyon. The essay part of this Lyon project simply documents a new media technologist’s (my) second-hand efforts to understand, consolidate, visualize and popularize ideas that have already been rigorously developed and explored by expert scholars utilizing primary source materials. Much of that material is held in archival repositories, has not been made available on the web, and might only be fully comprehensible to experts regardless.

The making of Le Plan Scénographique de Lyon c.1544-1550

One of the intriguing aspects of the 1550 Plan Scéno is that the 25 segments were printed using negatively-etched (Intaglio) copper plates, and those etchings were themselves compositions based on original survey drawings. Thus the 25 map sheets are copies of copies created through a process of mechanical reproduction. Neither the original survey drawings nor the copper engravings exist today, and while it is conceivable that other copies of the map were printed, this is the only known copy.

– Jeanne-Marie Dureau, Archiviste de la Ville de Lyon,

Introduction to Le Plan de Lyon Vers 1550 (1990)

The sheets were printed on “laid paper,” made by pouring paper pulp (made from linen or cotton) into a wire frame to dry. The Lyon Archives have identified the paper manufacturer’s shaped-wire watermark on some sheets, representing a bunch of grapes.

Creation date

The extant portions of the 1550 Plan Scénographique are undated and unsigned, but researchers have determined that the map was most likely created within the 8-year period between late 1544 and Spring 1553. It is likely that the principle survey drawings were created in 1544 (Gauthiez, 2010), but many features were added that are from a later period.

Here’s some date evidence that I was able to verify:

- In the top right of the map (sheets 4 and 5) workers are depicted building a new fortification, “c’est le boulevard de la Pye ou citadelle” (Grisard 1891, p.31). Gauthiez estimates that the map represents the progress of work on the new walls in approximately 1545.

- On sheet 6 is depicted a “jeu de paume” (early tennis) court decorated with Henri II’s crescent symbol and depicting four figures playing with rackets. This suggests that the map was worked on shortly before the Royal entry in September 1548 to celebrate Henri II’s coronation. According to Oxford scholar Richard Cooper, “late in June the order was given by [Governor of Lyon] Jean de Saint-André (for the construction of a new jeu de paume at Ainay on land bought from the abbot, Cardinal Gaddi)” (Cooper, p. 18, and Cooper’s source in the Lyon archives).

Ornamentation

The map’s ornamentation clearly follows the Fontainebleau tradition (essay in Heibrunn Timeline of Art History). The symbolism of the map is neoclassical rather than biblical, reflecting the Renaissance infatuation with classical imagery. It may also reflect an anti-clerical sentiment within Lyon’s secular aristocracy (Cooper, pp.3-5).

Through this project I have become something of an amateur enthusiast on 16th-Century French engraving – it doesn’t hurt that so much of it is now available online (hyperlink list) to augment Library holdings.

Symbolism

For a detailed analysis of the Plan Scéno’s symbolism and the messages it communicates, see Gérard Bruyère’s 1990 essay Notes sur les ornements du plan de Lyon au XVIe siècle, published as part of the Lyon Archives’ 1990 project. The symbolic elements can be viewed on the digital version of the plan (e.g., in the upper left, the Royal arms of France and Auster, the South wind).

Attribution

Little is known about the lives of even the most famous engravers of the 16th Century, the main evidence is in the art itself. Based on observation and the assistance of scholarship, here is a list of possible candidates for participation in the project, artists who may have had both the ability and opportunity to create the ornamental art of the 1550 Plan Scéno de Lyon, in approximate order of likelihood. Perhaps multi-spectral imaging analysis will someday reveal more information indicating who the artist(s) might have been.

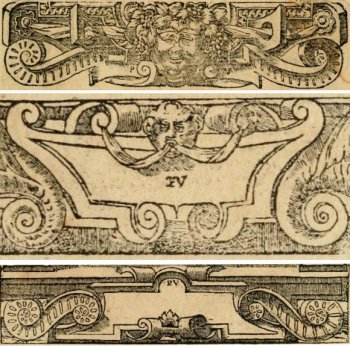

Cartouches from Alciato’s Emblemata (Lyon 1550), signed “PV” by Eskrich (for “Pierre Vase”)

- Pierre Eskrich, alias Pierre Vase, alias [Pierre] Cruche could have been the principal illustrator of the 1550 Plan Scénographique de Lyon both for the ornamentation and the map itself.

A Parisian who moved to Lyon around 1548, Eskrich created the woodcuts for a highly influential version of Andrea Alciato’s Emblems (a veritable cartoucherie published in Lyon in multiple editions from 1548-1551). Of equal interest is that in 1575 Eskrich engraved a map of Paris based on the Truschet-Hoyau 1550 plan (the Truschet-Hoyau map is discussed later in this essay). Eskritch’s Paris map was published in Francois de Belleforest’s La Cosmographie Universelle de tout le monde (Lyon 1575), a translation and update of an earlier Cosmographia by Sebastian Münster. Belleforest’s book also contains cartouches stylistically similar to those shown here from Alciato’s Emblemata. Other engravers contributed to La Cosmographie – for instance the contained Portrait of Lyon is credited to Antoine de Pinet, not Eskrich. - Georges Reverdy. “GE Reverdinus fecit”? Many scholars, notably Gérard Bruyère, have attributed the ornamentation (at least) to Reverdy, and Bruyère discussed why in depth. See Notes sur les ornements du plan de Lyon au XVIe siècle (1990).

- Étienne Delaune aka Stephanus. “Stephanus fecit?” He did a great deal of work (including goldsmithing) for and related to Henri II, and utilizes the king’s crescent moon symbol extensively. His style with cartouches, grotesques and more is consistent with the ornamentation of the Plan Scénographique. The images below are only two examples among the many attributed to Delaune in the Victoria & Albert Museum.

- Sebastiano Serlio (recent article attributing to Serlio the design of the temporary theatre built for Henri II’s 1548 entry to Lyon). Serlio was definitely in Lyon 1549-1550 and his longtime patron Cardinal Ippolito d’Este, Archbishop of Lyon, organized Henri II’s 1548 entry to Lyon.

- Jean Mignon. There are many artistic similarities between Mignon’s work and the 1550 Plan Scénographique’s ornamentation, and like most of the engravings attributed to Mignon, the Plan is unsigned (although the missing edges might have included a signature).

- Jacques I Androuet du Cerceau. Androuet du Cerceau was more than capable of creating both the ornamentation and the map itself (perhaps too capable). The contemporaneous and somewhat-similar Vue de la ville de Lyon en 1548 is traditionally attributed to Androuet du Cerceau – could the 1550 Plan Scéno and the 1548 view both be his work? This intriguing possibility is undermined by Estelle Leutrat’s convincing argument that the attribution of the 1548 view to Androuet du Cerceau is highly suspect (source: Leutrat 2007 pp.99-101). Could the two works be by the same person regardless of whether it is Androuet du Cerceau?

- Domenico del Barbieri (Fiorentino)

- Bernard Salomon

- Antonio Fantuzzi

For more expert analysis I recommend the work of Gérard Bruyère (who wrote about the map engravings for the 1990 Archives publication), Estelle Leutrat, and the Glasgow University Emblems Website.

Coloring the Map

While the two bottom cartouches are frustratingly empty on the Lyon Archives’ printing of the map (the only existing copy), many features of the map were colored in by hand, apparently shortly after the sheets were printed. Although the pigments have faded, the roofs of houses retain their color (most are red, ecclesiastical buildings are blue). Fields were colored green and the two rivers and other bodies of water were colored a dark blue (based on various patches of color that remain).

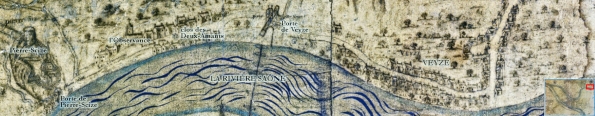

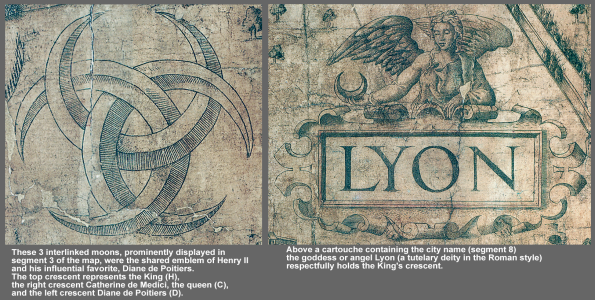

Topographical Features: Two Hills and Two Rivers

The faded blue pigment of the rivers is barely noticeable after four centuries, which makes it difficult to distinguish the two rivers from the surrounding landscape. This is very detrimental for considering the topography of a city like Lyon, which is so defined by being at the confluence of two rivers – the Saône (which meanders through the center of the city) and the faster-flowing, alps-born Rhône (which effectively served as the eastern border of Lyon up through the 16th century due to its unruly nature and frequent flooding). On the 1550 Plan Scéno the rivers are labeled as “LA SAONE” (female, called rivière, being a tributary) and “LE ROSNE” (male, called fleuve, not a tributary). The analogy between the joining of Lyon’s rivers at the confluence and the joining of a man and woman is used in the map’s imagery (see Bruyère, 1990), and is popular in both art and poetry (e.g., Délie, objet de plus haulte vertu, dizain XVII, Maurice Scêve, 1544). A further symbolic layer in the Plan Scéno emphasizes the importance of a proper and intimate relationship between the king, Henri II (the man) and the city of Lyon (the woman). The plan’s central cartouche shows the female angel (or tutelary goddess) of Lyon holding the king’s crescent symbol in the hand of her well-muscled right arm – fealty but also strength. (Bruyère 1990)

Distinguishing the rivers is so important for the map’s viewing that I have restored the blue of the water in Photoshop – this really brings the map back to life and makes the numerous river vessels “pop.” The color layer is non-destructive – in fact I superimposed the river engraving as well as any remnants of original color over my added semi-transparent blue layer. As the top image of this essay demonstrates, the enhanced water color can be toggled on or off based on user preference.

Here’s an example from sheet 13 which also shows how I addressed missing portions of the map for river areas such as the gap above the label for Port de Saint-Vincent [note that the image below shows an earlier too-blue waters version]:

For more historical information on Lyon and its waters:

- “L’eau et la santé à Lyon : la formation d’une cité – Partie 1” (Partie 2) by Vettorello Cécil and Vignau Marie (2010).

- Lyon et la Saône au XVIe siècle by Katharine Dana (2009)

As the altitude map above illustrates, the other defining features of Lyon’s topography are its two major hills, Fourvière (west of the Saône river) and La Croix Rousse (actually the beginning of a plateau stretching north of the low-lying Presqu’île). From our modern perspective, the scenic plan does a poor job of representing elevation, but perhaps cartographic artists in the mid-16th century were still figuring that out.

Dimensions

I calculated the compiled Lyon map’s full dimensions to be 170cm tall by 220cm wide (5’6.82″ x 7’3.21″) based on the published sheets that I digitized [Note: the Lyon Archives confirm this: “It consists of 25 sheets each, on average, 34cm high and 44cm wide. The assembly forms a rectangle 1.70m high by 2.20m wide.”]. For comparison, the contemporaneous and similar 15-plate “Copperplate Map” of London is believed to have been 112x226cm, 67.7% the size of the Lyon map (source).

Is the 1550 Plan Scéno the largest Early Modern axonometric map? Probably not – Jacopo de Barberi’s magnificent aerial-view map of Venice (c.1500), printed from a six-piece woodcut that took him three years to make, is 134×280.8cm. I calculate that Barberi’s map is a mere 0.2 square meters larger than the Lyon map (c’est la vie, n’est pas?).

For more on de Barberi’s Venice map (and on axonometric map creation in general) I enthusiastically recommend “Digitizing a complex urban panorama in the Renaissance: The 1500 bird’s-eye view of Venice by Jacopo de’ Barbari” by Juraj Kittler and Deryck W. Holdworth (New Media & Society, August 2, 2013).

Other Similar Renaissance Maps and Digital Projects

Thanks are due to R. Burr Litchfield for aiding the above map size comparison – his Florentine Gazetteer is a great digital project (and astonishing for way-back-when in 2006), accompanying his monograph Florence Ducal Capital, 1530-1630 (2008). Litchfield’s principal cartographic target is Stefano Buonsignori’s 1584 map of Florence, which is also being utilized in the University of Toronto’s newer DECIMA GIS project (as a backdrop for georeferenced data from the Florentine tax census of 1561-62, which they are inputting to a Filemaker database).

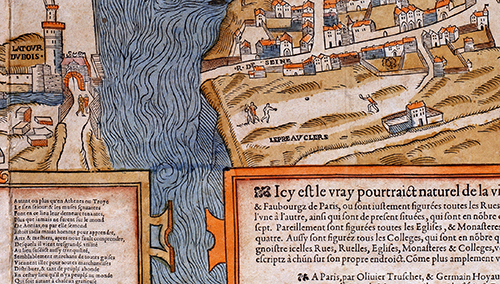

Another map that should be mentioned is Truschet and Hoyau’s “La ville, cite et universite de Paris,” which is contemporaneous (c. 1550-1552) to the Lyon plan (c.1550). The only known printing of the Truschet-Hoyau Paris map was rediscovered in the 1870s in Bâle, Switzerland (Cousin, 1875). The Truschet-Hoyau map printing is more complete than that of the Lyon map and available online via a fully-colored facsimile engraved and printed in 1980. This printing gives us more information on how the Lyon map might have looked if completed. The two maps share a westerly orientation, are extremely similar in engraving style, ornamentation and typeface, and warrant a closer comparison than I will give here. Perhaps the most interesting detail for this comparison is that unlike the Lyon map, the three cartouches at the bottom of the Truschet-Hoyau map are not empty – the left cartouche serves as a title box, the center contain a celebratory poem about Paris, and the right cartouche a map description. The most notable difference between the maps themselves is that the Truschet-Hoyau map only includes a few depictions of people and only one full vignette (the game, perhaps lawn tennis, shown in the detail below) as opposed to hundreds on the Lyon map.

The Truschet-Hoyau map of Paris is composed of 8 woodcut-printed sheets and measures 0.96m high by 1.33m wide, just over one-third the size of the 1550 Plan Scéno (Source:PICPUS).

Detail from “La ville, cite et universite de Paris” by Olivier Truschet and Germain Hoyau (c.1550-52) (1980 facsimile)

Other active digital projects exploring historical city maps include

- Map of Early Modern London (MoEML),

- Locating London’s Past and

- various Adam Matthew projects, particularly

London Low Life: Street Culture, Social Reform and the Victorian Underworld. - Imago Urbis: Giuseppe Vasi’s Grand Tour of Rome. This is the second of an ongoing three-stage project at the University of Oregon, the first of which created the Interactive Nolli Map, a digital adaption of Giambattista Nolli’s La nuova topografia di Roma Comasco(106x208cm, 12 plates,1748) and will continue with the upcoming Open Rome: A Spatial History. The Vasi project uses Nolli’s 1748 map of Rome as an interface for exploring Vasi’s contemporaneous scenic views of the city. It is well done. I feel somewhat competitive, because they are exploring many of the things I am, both on renlyon.org (this project) and in my Vectis Scenery project, which is also a map-as-interface scenic tour utilizing text and landscapes also created, printed and published by the map’s engraver, George Brannon. I composed summary images for both digital projects, which are somewhat similar:

They have chosen to create original commentary on each engraving, whereas most of the written content in Vectis Scenery is written by the artist himself. The Vasi tour of Rome has also created excellent viewshed icons to indicate the area depicted in each engraving and the angle from which it is viewed.

A lot of interesting work out there!

The Digital Plan Scénographique de Lyon (c.2014-15)

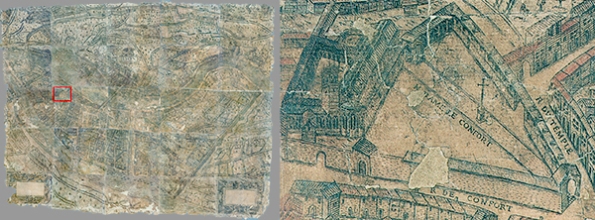

The two images below illustrate the high level of detail and impressive (maybe excessive) scale of the 1550 Plan Scéno. The left image is a full view of the digitally-compiled map. The red rectangle indicates the zoomed area shown in the right image. This shows that the map is not simply large but also intricate and informationally dense. The left image of the full map appears blurry, but that is because it is actually less than 1% the size of the full 2.5 gigapixel image, and this right-side image is still less than 3/4 the size of the original (~21% zoom). Note that in the online version, ~33% zoom approximates the map’s real-world size, while 100% zoom shows the map three times larger than the original.

If I were a mathematician, I’d try to calculate how far away a person would need to be from a 2.2-meter wide object for it to appear the same size as a 0.12 meters wide photo of the map held by the viewer at arm’s length.

I’m not going to hazard it at this point (let’s just say it’s percolating – I would have to calculate its “angular size”).

My first effort to digitally compile the Plan Scénographique (Winter 2013-14) resulted in an impressive-sounding 4,900-pixels-wide image, but the actual resolution was less than 10% of the 25 full-sized segment scans I created (52.28ppi, down from 500ppi). If I had tried to compile the map using the 25 full-size TIFF images (each 7,000 pixels wide at 500ppi), my work PC computer would have crashed. This matters because my first version lacked much of the rich detail that makes the Plan Scéno exceptional. For example, the creator(s) labels most of the streets and churches on the map but the text is illegible in the small, 52.28 pixels-per-inch version.

In April 2014, I re-compiled the map from the full-sized images utilizing a more powerful PC computer. My current version is a 2.5 gigapixel image with over 400ppi resolution, and all the writing is fully legible. At some point I will probably re-process the map a third time using slightly better scans, but the current image is more than adequate for exploring the map.

In 2020 the Lyon Archives generously shared digital photographs of the 1550 plan taken in 2018. I am currently finalizing an improved digital version utilizing these superior images and benefiting from my own greater understanding of the subject and improved imaging skills (July 2021).

Historical Context

The Italian Wars

The period known as the French Renaissance is generally thought to have begun with the first of France’s “Italian Wars,” Charles VIII’s invasion of Italy (1494-8), which introduced many aspects of the Italian Renaissance to the French. Six more Italian Wars followed over the next 61 years, with France’s imperial pretensions being repeatedly thwarted by the Habsburgs of the Holy Roman Empire and Spain. I should mention that Lyon was known as the “Clé du Royaume” of France during this period, being in a strategic position between Isle-de-France (Parisian region) and the Italian alps and therefore a logistical center for military campaigns into Italy.

Lyon was the second largest city in France during the 16th Century (approximate population 80,000, compared to Paris’ population of at least 250,000) and the major trading hub of Southern France (reference). Up until the 1550s Lyon was visited frequently by the King’s court and was the base of operations for Francois I’s Italian campaigns.

Ironically Francois I (ruler of France from 1515-1547) borrowed heavily from Lyon’s expatriate community of Italian bankers to finance his military campaigns into Northern Italy. Italian merchants were also prominent in Lyon’s fairs and the silk industry, and many of their impressive residences are depicted on the 1550 Plan Scéno. Sixteenth century Lyon was truly a multi-ethnic, cosmopolitan city of strategic importance for both trade and war.

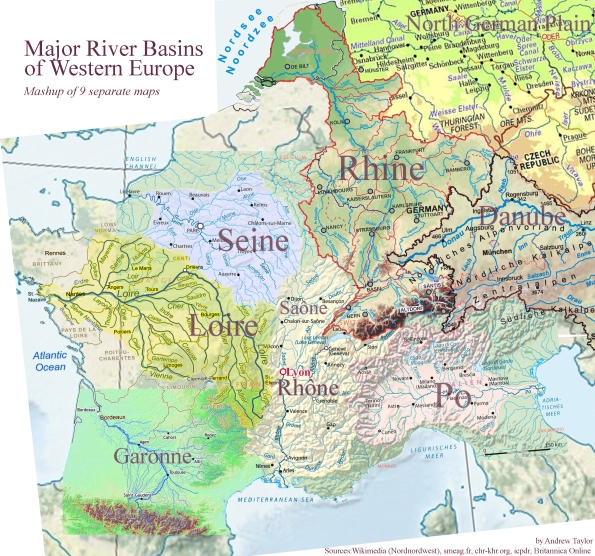

To illustrate this I put together the following quick “mashup” of major river basins in Western Europe centered on Lyon. Despite obvious imperfections, it does show that Lyon was strategically located near 5 major river systems – The Loire, Seine, Rhine, Rhone (includes Saône) and Po. One can visualize Francois I’s forces in 1524-25 embarking from Lyon towards Grenoble, across the alps at Briançon, though the Susa valley to Turin, then down the Po river towards Pavia (and defeat).

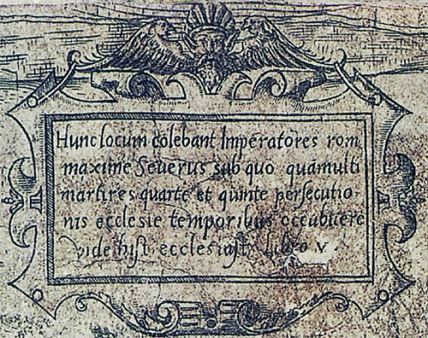

Roman Lugdunum

The 1550 Plan Scéno explicitly references Lyon’s own Roman past – almost a millenium earlier – to reflect imperial glory on the French crown and Lyon itself. Lyon was built upon the ruins of Lugdunum (c. 43BCE-192CE), the Roman Capitol of “the three Gauls” – Celtica, Belgica and Aquitania. The Roman city was mostly destroyed in the Battle of Lugdunum (197CE), the victory that solidified Emperor Septimius Severus’ control of the Roman Empire. Severus founded his own imperial dynasty, which is what the 16th Century French Kings aspired to (particularly Francois I) with questionable success.

The following cartouche (link) is from the 1550 Plan Scéno’s eighth sheet, centrally located on the hill of Fourvière, which was the heart of Lugdunum.

| Jacques-Jules Grisard’s Latin-to-French Translation (1891) |

Latin-to-English Translation |

| Ce fut le séjour aimé de plusieurs empereurs de Rome, notamment de l’empereur Sévère. Sous son règne, de nombreux martyrs, dans la quatrième et cinquième persécution contre les chrétiens furent misa mort. (Voyez l’histoire ecclésiastique, livre 5.) | This was the beloved residence of several emperors of Rome, especially Severus. Under his reign, many martyrs were killed in the fourth and fifth persecutions of the Christians. (See History of the Church, book 5.) |

Henri II

The 1550 Plan Scéno also contains numerous symbolic references to Henri II, who ruled France from March 1547 until his premature death in June 1559. This tells us that at least the artistic, non-cartographic elements of the map were created after Henri II was crowned King of France in July 1547 (succeeding his father Francois I). While some map elements may date to as early as 1544, the Plan Scéno was most likely completed around the time of the King’s Royal Entry into Lyon in September 1548. The artwork created for the Royal Entry contains classical imagery and symbolism extremely similar to that used in the Plan Scéno (as shown in a festival book for the entry written by the celebrated poet and humanist Maurice Scêve and illustrated by Bernard Salomon). Henri II’s personal emblem, the crescent moon, is pervasive in both book and map.

Scêve and the artist Bernard Salomon (whose engravings illustrate the festival book) helped orchestrate the 1548 Royal Entry itself, which was primarily funded by the powerful and wealthy Archbishop of Lyon, Ippolito d’Este (later Cardinal of Ferrar). This is quite an intriguing line of inquiry as well – did these men also play a part in arranging the creation of the Plan Scéno itself? (more info.)

Ces entrées sont des phénomènes multimédia qui demandent toute une équipe : architecte, peintres, sculpteurs, metteurs en scène pour les saynètes, architriclin pour les banquets, costumier, décorateur pour la scénographie ; humaniste/historien/poète qui conçoit les grands thèmes, compose les inscriptions, les dialogues, et sera chargé par les édiles du livret officiel. – Richard Cooper (2019)

In July 1559, at a tournament held to celebrate the Peace of Cateau-Cambrésis that ended the last of the Italian Wars, Henri II was killed when a splinter from a broken lance flew into his visor during a joust and the injury became infected. Henri II’s teenage son Francis II inherited the throne, and as a result the politics of France were destabilized.

The end of the Italian Wars did not bring peace to France. Three years after Henri II’s death, the Massacre of Vassy instigated the first of the mostly-internal French Wars of Religion between Catholics and Protestant Huguenots, which continued for almost forty years, at least until the Edict of Nantes in 1598.

In 1562, during the first War of Religion, the Protestant (Calvinist) Huguenots took over Lyon, pillaged its many Catholic churches, and demolished two – the Basilica Saint-Just and L’église Saint-Irénée, shown in the first (top-left) sheet of the 1550 Plan Scéno. The churches were located southwest of the city walls, and the pillaged stones from Saint-Just were used to reenforce the fortifications of the city. Saint-Irénée was rebuilt on the same site in 1582. A new Église Saint-Just was built, but to the north of the original site, just within the main city walls. Today the ruins of the original Saint-Just have been developed into “en jardin archéologique” (Église Saint-Just et nécropole).

Thus, we can see that 1550 Plan Scénographique represents the city of Lyon mostly at peace and part of a (relatively) unified France shortly before the onset of a long period of traumatic internal strife.

Portrait of a Living City

While many similar scenic maps from the sixteenth century depict scenes of city life, those in the 1550 Plan Scénographique de Lyon are more pervasive, varied and evocative than those of other axonometric city portraits that have come down to us.

The engraver peppered the map with a great many delightful little stick-figure vignettes – idealized representations depicting everyday activities such as hunting, fishing, farming, building fortifications, bartering, dancing, and even tennis. In addition the map features innumerable trees and numerous wild and domestic animals of various types. Scholar Jacques Roussiaud estimates that the map shows 440 human figures (90% adult male) and 130 animals with horses and dogs being most prevalent (Roussiaud, 1990).

The ubiquitous live vignettes are what truly distinguish the 1550 Plan Scénographique de Lyon from other similar scenic maps. These scenes from life add a powerful dynamic element, evoking an idealized era of prosperity, and inspiring curiosity in the viewer about how people lived during the now-romanticized “golden age” of mid 16th-century Lyon.

Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard

Are sweeter; therefore, ye soft pipes, play on;

Not to the sensual ear, but, more endear’d,

Pipe to the spirit ditties of no tone:

Fair youth, beneath the trees, thou canst not leave

Thy song, nor ever can those trees be bare;

Bold Lover, never, never canst thou kiss,

Though winning near the goal yet, do not grieve;

She cannot fade, though thou hast not thy bliss,

For ever wilt thou love, and she be fair!

– John Keats, Ode to a Grecian Urn (1819)

– Andrew Taylor, 01/07/14

Addendum

Other Digital Projects about Pre-Modern Lyon

An interesting GIS project would be to create a virtual 1550 Lyon based on various sources and implemented using a software platform such as Esri’s CityEngine. Many projects like this are already being worked on (most notably Lyon en 1700) so I expect a virtual pre-modern Lyon to become available online within the next decade.

[Note: The Lyon GIS project is already well underway – an authoritative, scholarly, data-driven historical project, not merely a cavalier visualization!]

Description of the map in French on the Lyon City Archives website.

A series of 25 engravings based on the 1550 Lyon plan was created and published in serial from 1872-76 as Plan scénographique de la ville de Lyon au XVIe siècle. Research by the Lyon Archives tells us that architect Léon Charvet directed the project and that it was executed by two engravers – Joanny Séon (the topographical engraver) and François Dubouchet (the ornamental engraver). Note that while the facsimile was printed at the same size as the original, it was engraved on zinc plates, whereas the 1550 Plan Scéno was engraved on copper plates.

At one point I had believed that the full-map image shown below was of an additional (extra) 26th sheet engraved for the 1870s project – an overview image of the whole map with the missing edges reconstructed (based on the little information available from other sources). However my own work (and a careful viewing of the below map) disproves this – the image below was compiled from reductions of the 25 full-size engraved copies made in 1872-1876 for the “facsimile” edition. The below reduction of the facsimilé may have been made for or by Lyon’s Museum Gadagne (which has a full-size printing of the 1870s facsimile on permanent exhibition), or may be a version of the 1940 reduction published in the municipal archives’ 1990 project Lyon en 1550. Unfortunately the reduction image is much too small for the street and building labels to be legible. An illegible stamp on the lower right and an accession number on top are modern archival details.

I am somewhat skeptical about the lettering on the four reconstructed sides, which don’t perfectly match what remains of the original. Only a few remnants of the edges’ lettering remain, on the first sheet (top-left).

Here is the Latin writing as shown along the edges of the 1876 facsimile:

The vertical letters:

Left side: “Pars Meridionalis” (Southern part).

Right side: “Pars Septentrionalis” (Northern part).

The horizontal letters:

Top: “Pars Occidentalis” (West Part)

Bottom: “Pars Orientalis”(East part)

These side labels copy Tardieu’s 1698 map (see below) but we don’t know how well they match up with those on the original 1550 map which no longer exist. There are partial letters still visible at the top of the first (top-left) sheet of the original plan, but they do not line up with those of the 1876 facsimile.

An additional primary source for the 1872-76 “Facsimile” and other later derivative maps is the excellent 1698 reduction engraved by Nicolas-Henri Tardieu for scholar Claude-François Ménestrier. Although smaller (68x86cm, less than 1/6th the size of the original), lacking the two bottom cartouches, and less detailed, the “Tardieu map” is clearly based on the 1550 Plan Scéno map, and in 1783 was even incorrectly considered the original, with the 1550 original believed to be a copy of it. It is worth noting that the Tardieu plan does a far better job of representing elevation than the original map does (at least in it’s current condition). The Tardieau plan the best of the derivative copies and a great reduction, despite having at least one significant error (a label by Menestrier stating that Les Terreaux had been the site of a canal between the Rhône and the Saône during Roman times, this is probably incorrect). For a discussion of this see Benoît Vermorel’s “Historique des anciennes fortifications de Lyon entre les Terreaux et la Croix-Rousse” (pp. 9-16, Jan. 1881).

Unlike the 1870s reconstruction, the bottom right corner of Tardieu’s version doesn’t show the North-Northeast wind’s face, or the scroll containing “Aquilo” (the wind’s classical name), but the 1550 Plan Scéno still contains remnants of a scroll matching those visible in the other three corners, and perhaps part of the breath emanating from the cherub’s mouth. For this area, the 1870s facsimile is copying Moithey’s 1783 plan (in many ways the worst of the derivative plans). The original 1550 plan can be explored side-by-side alongside all of the derivative plans on my renlyon.org website (http://www.renlyon.org/Comparison.html) and the many differences can be easily identified.

Paul Fuega’s 2007 article “Faire revivre le plan scénographique” explores the brief history of the “Société de topographie historique de Lyon” that created the facsimile. For a number of reasons (not the least of which is accessibility) the facsimile continues to be used as a surrogate for the original map today, usually without any acknowledgement (or perhaps awareness) that the displayed image is a nineteenth-century recreation with significant differences from the original. This is one of the issues addressed by the renlyon.org project this essay is a part of.

When the Lyon Archives published the 25 sheets in 1990, city archivist Jeanne-Marie Dureau (who oversaw the project) wrote “Historique du plan de 1550” an essay explaining how the 1872-76 facsimile came to replace the original in the public imagination. Dureau expressed the hope that the 1990 publication of the original sheets would redress this, but my own web research has shown me that, 25 years later the 1872-76 facsimile remains pre-eminent. Dureau’s essay is now part of the Archives Municipales de Lyon’s excellent Lyon 1550 webpage (taken offline but still available at the Internet Archive) which adapts the 1990 publication, including additional scholarship as well as a very low-resolution version of the full 1550 map. Dureau expressed the hope that the 1990 publication of the original sheets would encourage use of the original by scholars, but my own research has shown me that, 25 years later, the 1872-76 facsimile remains pre-eminent. Now with the original map now available online alongside the facsimile, scholars have the option of using images derived from the original map, those of the clearer but slightly-inaccurate 1872-1876 copy (which has no coloring), or both. http://www.renlyon.org/Comparison.html allows anyone to compare the two versions along with four other historical derivatives, all far earlier than the facsimile. I also go into greater detail regarding the “afterlife” of the plan, drawing heavily from scholarly sources.

Andrew Taylor standing behind the 25 sheets as restored in 1989 by Michel Guet, photographed by Jacques Gastineau and published by Archives Municipales de Lyon in 1990.

fantastic and fascinating…

Thanks Mark, ditto for Quarentia!

Merci Damien!