Archive

Historic Map Compiling Project – Le Plan Scénographique de Lyon

– Gigapixel image of the compiled full map browseable in Zoomify viewer

– Side-by-side comparison of the 1548 map with five historical derivatives

– High-resolution 3D (bird’s-flight) video tour of the full map

In January 2014 I digitally optimized and compiled the 25 separate sheets that together make up “Le Plan Scénographique de Lyon vers 1550,” a huge, highly-detailed, 16th-Century axonometric (bird’s-flight view) map depicting the French city of Lyon cc. 1544-53 CE. Since then I’ve been working to understand and contextualize this curious historical artifact, and this essay is one product of that effort.

The Archives municipales de Lyon holds the only known copy of the 1550 Plan Scéno (as I’ll call it here, though many of the preparatory drawings likely date to 1544). In 1989 preservationist and paper expert Michel Guet dismantled and restored the map. This involved detaching the 25 sheets from their paper backing and each other as well as removing the remnants of earlier flawed restoration efforts. In 1990 the Lyon Archives published photographs of the 25 separated and restored map sheets along with an accompanying volume of scholarly essays (later augmented with a second set of essays). All of the essays from the project were hosted on the Lyon Archives’ website for years and are still accessible via the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine. If any photographs exist of the plan taken before Guet’s 1989 restoration they have not been published by the Lyon Archives.

The map segments are to be arranged for viewing in a 5 by 5 grid starting from the top left, each segment being overlapped by the segments to the right and below it. Because each segment of the published map is larger than the flatbed scanner I used, I originally scanned each segment in two parts at 600 ppi, combined them, and then reconstituted the full map using Adobe Photoshop (info tooltip | link).

Viewing the map’s 25 segments separately, it is very difficult to effectively view or even fully conceptualize the map in its totality, as a single composition. To redress this I determined to compile the 25 map segments into one contiguous digital image. I should note that significant image adjustment (aka warping) was required in some areas to insure that the segments line up logically and so the final product would appear seamless. You’ll notice that the bottom-right cartouche is slightly lower than the one on the lower left. This may not be a characteristic inherent in the original, but could reflect the digital processing – I mostly compiled each row of sheets starting from the top-left, following the original numbering of the 25 sheets, and therefore the bottom-right sheets were the last added to the composition.

For modern viewers, the faux-aerial perspective used for pre-modern axonometric city maps is strikingly similar to the satellite-derived views provided by modern online map services (though the top of the the 1550 Plan Scénographique is primarily directed west-southwest, not north). For comparison, below is a high-contrast screenshot of Bing maps’ “Bird’s Eye view” of modern-day Lyon (facing west) compiled from multiple aerial photographs taken at an oblique 45-degree angle (unfortunately this bird’s eye view is now only available via the Windows Maps desktop app – AT 02/21)).

Note that the modern shape of central Lyon is significantly different from that shown in the 1550 Plan Scénographique. This is primarily because of the largely-industrial Perrache neighborhood, extending South (left) of the highway in the modern center of the Presqu’île (peninsula), which did not exist in the 16th century. Perrache was developed from 1779-1840, incorporating southern marshland and small islands into the peninsula and moving the confluence of the Saône and Rhône rivers further downstream (source). In the sixteenth century, these low-lying islands were repeatedly flooded, destroyed, and rebuilt by the rivers. Only the edge of the area now covered by Perache is shown on the 1550 Plan Scéno, an island labelled “[BRO]TEAUX D’ENEY” in reference to the nearby Abbaye d’Ainay. I haven’t attempted to recreate how Broteau D’Ainay might have looked in 1548, but it can be seen on Philippe Le Beau’s 1607 Lyon map (optimized detail view with label indicated). Source: archives municipales de Lyon.

See Gauthiez (2010) for more on Perrache and the confluence and Arlaud (2000) for much more on the Presqu’île.

Lyon Topographic Plan, 1544 & 2015

The animated map above is an augmented “mashup” incorporating three sources –

- A blueprint of Lyon in 1544 (identified as a/the main year during which the Plan Scénographique’s survey drawings were made) adapted from a Flash presentation accompanying the Lyon Archives’ 2009 exhibit Lyon 1562: Capitale Protestante (B. Gauthiez) superimposed on

- Geoportail‘s amazing elevation map (“Carte du Relief” layer, unfortunately there was no altitude legend), facing west and extended North and South, and

- a 2015 satellite image exported from Google Earth Pro.

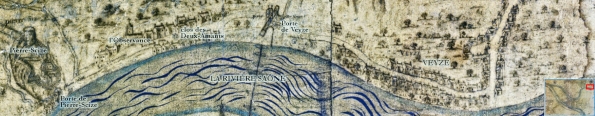

An observation about the above GIF – I originally labeled the top-right neighborhood (quartier) around Le Couvent l’Observance “Vaise.” Vaise is actually the name of the faubourg (suburb) located outside Lyon’s northern city gate (“Porte de Vaise“), situated on a plain north of l’Observance and west of the Saône river which was mostly farmland in the mid-1500s. During the 16th century the area around l’Observance was named “Le clos des Deux-Amants” after a Roman-era funeral monument shown on the Plan. (source: Les Cordeliers de l’Observance á Lyon, par L.A.A. Pavy et [C.] Tissseur, 1836, pp.6-11).

Click here to see the area on the digital Plan Scéno (top half of sheet 10), and from there you can switch to the 1698 and 1876 derivative maps (select from lower-left pulldown menu) to see the now-missing part of the 1550 Plan Scéno showing the approach to Vaise.

Where Lyon ends and Vaise begins is confusing because it changes over time. As Lyon grew northward the city would build a new city gate and absorb the part of “Vaise” located south of the gate. In 1550, the city gate labeled the “Porte de Pierre-Scize” on the 1550 plan was the northernmost city gate of Lyon and was sometimes referred to as the “Porte de Vaise.” In 1580, another gate was built at a point just north of the edge of the 1550 plan and this gate becomes the “Porte de Vaise” (it would also sometimes be called “Porte du Lyon” or “Porte neuve du Pont Levis” (source).

This annotated detail taken from LeBeau’s non-derivative 1607 map of Lyon extends further north than the 1550 plan and shows more of Vaise (a half-century later):

“Why not georectify the Plan Scéno, since we know where most of the represented landmarks were located, maybe even all of them?”

Because the map is far from spatially accurate. The area of the W-SW-facing map overall appears to be significantly stretched N-S (the X-Axis) compared to the real-world dimensions. This uneven stretching is most notable in the bend of the Saône river as it rounds the central hill of Fourvière, which is far less sharp than in the real world. This may have been deliberate artistic license rather than a mistake, as the elongation allows the cartographer more left-right room to include location-based labels and imagery, particularly along the densely-settled banks of the Saône. It also would reflect the viewpoint of an artist situated on the hillside of La Croix-Rousse, looking south across the Saône towards Château de Pierre-Scize making preparatory sketches. Scholars have also observed that while many buildings had as many as five or six floors, the map shows no building as having more than four.

While I do believe that the 1550 Plan Scéno de Lyon achieves verisimilitude as a portrait of the city (achieves the appearance of spatial accuracy), it’s building imagery is not completely reliable, and both its scale and compass directionality are wildly inconsistent.

This plan was drawn up by calculating angles from certain heights, particularly church towers such as that of Saint-Nizier which, located on the peninsula, has often been used for this purpose. These calculations were then compared with distances on the ground, measured by using a knotted rope or by counting the number of steps…in the geometric center of the plan was the ditch, drawn according to a scale of 1/824. All around, everything is out of proportion in order to include certain elements considered essential. If the [1/824] scale had been used throughout, the plan would have been 3.5 times bigger!

—Musée Gadagne, A plan depicting scenes of 16th C. Lyon, Inv. N 1675

Geographer and urbanist Bernard Gauthiez, the de facto topographical biographer of Lyon for the past twenty years, expressed it to me thus:

“Georectify[ing] the 1544 plan [is] like mapping the Near East from the Bible… Several scales are used, and it has not been drawn from a measured survey. See my paper on it.”

Professor Gauthiez’ work on Lyon (along with the Archives Municipales’ 1990 publication) is an authoritative modern source for many of the ideas I am exploring regarding the topography and urban development of pre-modern Lyon. The essay part of this Lyon project simply documents a new media technologist’s (my) second-hand efforts to understand, consolidate, visualize and popularize ideas that have already been rigorously developed and explored by expert scholars utilizing primary source materials. Much of that material is held in archival repositories, has not been made available on the web, and might only be fully comprehensible to experts regardless.

The making of Le Plan Scénographique de Lyon c.1544-1550

One of the intriguing aspects of the 1550 Plan Scéno is that the 25 segments were printed using negatively-etched (Intaglio) copper plates, and those etchings were themselves compositions based on original survey drawings. Thus the 25 map sheets are copies of copies created through a process of mechanical reproduction. Neither the original survey drawings nor the copper engravings exist today, and while it is conceivable that other copies of the map were printed, this is the only known copy.

– Jeanne-Marie Dureau, Archiviste de la Ville de Lyon,

Introduction to Le Plan de Lyon Vers 1550 (1990)

The sheets were printed on “laid paper,” made by pouring paper pulp (made from linen or cotton) into a wire frame to dry. The Lyon Archives have identified the paper manufacturer’s shaped-wire watermark on some sheets, representing a bunch of grapes.

Creation date

The extant portions of the 1550 Plan Scénographique are undated and unsigned, but researchers have determined that the map was most likely created within the 8-year period between late 1544 and Spring 1553. It is likely that the principle survey drawings were created in 1544 (Gauthiez, 2010), but many features were added that are from a later period.

Here’s some date evidence that I was able to verify:

- In the top right of the map (sheets 4 and 5) workers are depicted building a new fortification, “c’est le boulevard de la Pye ou citadelle” (Grisard 1891, p.31). Gauthiez estimates that the map represents the progress of work on the new walls in approximately 1545.

- On sheet 6 is depicted a “jeu de paume” (early tennis) court decorated with Henri II’s crescent symbol and depicting four figures playing with rackets. This suggests that the map was worked on shortly before the Royal entry in September 1548 to celebrate Henri II’s coronation. According to Oxford scholar Richard Cooper, “late in June the order was given by [Governor of Lyon] Jean de Saint-André (for the construction of a new jeu de paume at Ainay on land bought from the abbot, Cardinal Gaddi)” (Cooper, p. 18, and Cooper’s source in the Lyon archives).

Ornamentation

The map’s ornamentation clearly follows the Fontainebleau tradition (essay in Heibrunn Timeline of Art History). The symbolism of the map is neoclassical rather than biblical, reflecting the Renaissance infatuation with classical imagery. It may also reflect an anti-clerical sentiment within Lyon’s secular aristocracy (Cooper, pp.3-5).

Through this project I have become something of an amateur enthusiast on 16th-Century French engraving – it doesn’t hurt that so much of it is now available online (hyperlink list) to augment Library holdings.

Symbolism

For a detailed analysis of the Plan Scéno’s symbolism and the messages it communicates, see Gérard Bruyère’s 1990 essay Notes sur les ornements du plan de Lyon au XVIe siècle, published as part of the Lyon Archives’ 1990 project. The symbolic elements can be viewed on the digital version of the plan (e.g., in the upper left, the Royal arms of France and Auster, the South wind).

Attribution

Little is known about the lives of even the most famous engravers of the 16th Century, the main evidence is in the art itself. Based on observation and the assistance of scholarship, here is a list of possible candidates for participation in the project, artists who may have had both the ability and opportunity to create the ornamental art of the 1550 Plan Scéno de Lyon, in approximate order of likelihood. Perhaps multi-spectral imaging analysis will someday reveal more information indicating who the artist(s) might have been.

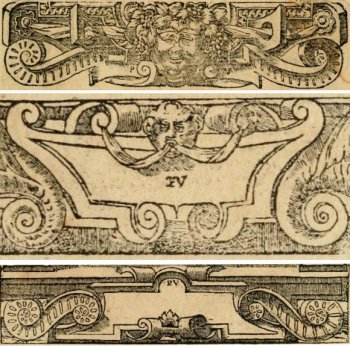

Cartouches from Alciato’s Emblemata (Lyon 1550), signed “PV” by Eskrich (for “Pierre Vase”)

- Pierre Eskrich, alias Pierre Vase, alias [Pierre] Cruche could have been the principal illustrator of the 1550 Plan Scénographique de Lyon both for the ornamentation and the map itself.

A Parisian who moved to Lyon around 1548, Eskrich created the woodcuts for a highly influential version of Andrea Alciato’s Emblems (a veritable cartoucherie published in Lyon in multiple editions from 1548-1551). Of equal interest is that in 1575 Eskrich engraved a map of Paris based on the Truschet-Hoyau 1550 plan (the Truschet-Hoyau map is discussed later in this essay). Eskritch’s Paris map was published in Francois de Belleforest’s La Cosmographie Universelle de tout le monde (Lyon 1575), a translation and update of an earlier Cosmographia by Sebastian Münster. Belleforest’s book also contains cartouches stylistically similar to those shown here from Alciato’s Emblemata. Other engravers contributed to La Cosmographie – for instance the contained Portrait of Lyon is credited to Antoine de Pinet, not Eskrich. - Georges Reverdy. “GE Reverdinus fecit”? Many scholars, notably Gérard Bruyère, have attributed the ornamentation (at least) to Reverdy, and Bruyère discussed why in depth. See Notes sur les ornements du plan de Lyon au XVIe siècle (1990).

- Étienne Delaune aka Stephanus. “Stephanus fecit?” He did a great deal of work (including goldsmithing) for and related to Henri II, and utilizes the king’s crescent moon symbol extensively. His style with cartouches, grotesques and more is consistent with the ornamentation of the Plan Scénographique. The images below are only two examples among the many attributed to Delaune in the Victoria & Albert Museum.

- Sebastiano Serlio (recent article attributing to Serlio the design of the temporary theatre built for Henri II’s 1548 entry to Lyon). Serlio was definitely in Lyon 1549-1550 and his longtime patron Cardinal Ippolito d’Este, Archbishop of Lyon, organized Henri II’s 1548 entry to Lyon.

- Jean Mignon. There are many artistic similarities between Mignon’s work and the 1550 Plan Scénographique’s ornamentation, and like most of the engravings attributed to Mignon, the Plan is unsigned (although the missing edges might have included a signature).

- Jacques I Androuet du Cerceau. Androuet du Cerceau was more than capable of creating both the ornamentation and the map itself (perhaps too capable). The contemporaneous and somewhat-similar Vue de la ville de Lyon en 1548 is traditionally attributed to Androuet du Cerceau – could the 1550 Plan Scéno and the 1548 view both be his work? This intriguing possibility is undermined by Estelle Leutrat’s convincing argument that the attribution of the 1548 view to Androuet du Cerceau is highly suspect (source: Leutrat 2007 pp.99-101). Could the two works be by the same person regardless of whether it is Androuet du Cerceau?

- Domenico del Barbieri (Fiorentino)

- Bernard Salomon

- Antonio Fantuzzi